Over the course of this school year, I've learned about a lot of different teaching methods and ideas about which I wasn't previously aware. I've been trying some of them in my own classes (21st century skills, crowdsourced grading, increased prominence of blogging, etc.) but there has been one that has intrigued me quite a bit that I have yet to implement and that's game based learning. Gartner, Inc. has predicted that "by 2015, more than 50 percent of organizations that manage innovation processes will gamify those processes." Since the same principles seem to make sense in an educational setting, I've been toying with ideas in my mind about how to make it work within the context of my classes. I've had some ideas but what usually gets in the way is trying make a game that fits the MYP Technology curriculum and adequately addresses each criterion. With this in mind, I eagerly attended John Rinker's session on game based learning.

photo credit: Toni Blay via photopin cc

John had taken a game based approach to learning about the history of the Neolithic revolution. To investigate the essential question ‘How does WHERE we live affect HOW we live?’, Rinker's class undertook a range of challenges, split into levels of achievement, that blended investigation of the content with investigation and skill development in Google Earth. An advantage to game-based learning is that it can help to keep an appropriate focus on the concept of the unit of work rather than on the tools used to present it. As Rinker points out in his blog, "This project isn’t about using the tool, it’s about creating an authentic experience to demonstrate an understanding of our essential question." This is what can really help me effectively apply game based learning to the MYP Technology Design Cycle.

As is the nature of the Design Cycle, despite the "creating" criterion being a relatively small component of the curriculum (maybe about a fifth of the criteria), it tends to take up a lot of time with learning specific tools (in the case of most of my classes, that refers to digital tools) and applying those skills. Getting students to complete levels is an interesting way to get them to do more "dry" work like research in order to add some motivation to unlock the next level which may include learning or applying skills in a particular program. As the school year is nearing its end, I have managed to assess my Year 8s on all the required criteria at least once already so this leaves me a little more free to experiment with new ideas with my students. Typically, at this point of the trimester, my Year 8s would be starting a relatively brief 'design and make' project, using Flash animation software to create an eCard. As I was riding a bus recently, I jotted down an outline of how to take what is typically a pretty straightforward little unit and gamified it. I tried to alternate between Flash skills and other design cycle criteria. Here's an outline of what I have come up with so far:

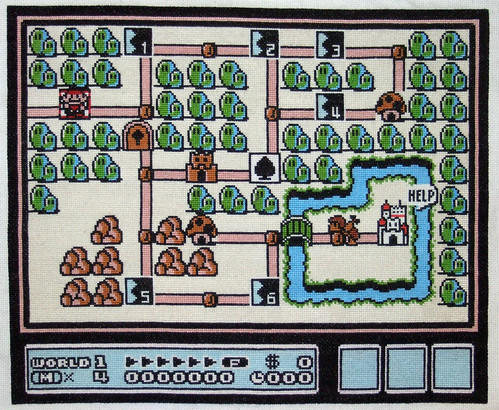

Level 1 - Animate a Bouncing Ball. Students will follow along to a video tutorial I created last year to help animate a bouncing ball.

Level 2 - Type out possible ideas for their eCard and post it to their blog.

Level 3 - Get a star to follow a particular path while continuously changing colour.

photo credit: Cross-stitch ninja via photopin cc

Level 4 - Write Design Specifications for a successful eCard and post it to their blog.

Level 5 - Make your name transform into a shape

Level 6 - Pick one idea for your eCard and draw a simple storyboard to explain the action

Level 7 - Make the eCard

Level 8 - Make your animation file available through your blog

Level 9 - Support others with their eCards

So far, these are just skeletal instructions for each level and more specific instructions and requirements will be added. I am still toying with the idea of how to distribute each level to students who have successfully completed the work. An email containing the next level's instructions is one, simple way but I'm also considering having a password protected blog post for each level as well. Another thing to consider is a tracking sheet so that students can easily (and preferably visually) track their progress.

There are a few challenges to using this approach for student projects. One problem I've already alluded to earlier is that it can be difficult to present adequate/interesting challenges that still address the different bands of achievement on the curriculum rubrics. For this particular unit, I am making sure that students do address the different parts of the rubric but I think it will still be up to my professional judgment as to what level of achievement they've demonstrated for a given criterion. In the planning of future units of work though, I could foresee this as a great way to differentiate a unit of work. The earlier levels represent lower bands on the rubric and as the students succeed to high levels, they will begin to demonstrate evidence of criteria from the upper mark bands. Some students may not actually complete all the levels but for the more keen or capable students, this gives them the opportunity to take their work to a higher level without being held back by other students that do not progress as quickly.

Probably the biggest challenge involved in setting up a unit like this is the planning required for it to work successfully. Thankfully, for this first attempt at a game based learning unit, I already have a number of resources to build upon which makes it a more manageable task at this time of the year. Also, on the plus side, initiating such careful planning early on also means that once the unit is underway, I should, in theory, have a fair bit of time to manage the game and support students in their attempt to complete each level.

I'm looking forward to seeing how this works out and am certain that I will run into challenges along the way but I'm sure that things will work out on the whole and any problems that arise will simply help me to make improvements to units of work for next school year.